On numbers, structure and induction

In "The miracles that matter", Mircea Popescu gives a beautiful description of numbers, starting from set-theoretical constructs and building the sets of numbers we are so used to: naturals and integers, fractional numbers, and finally, real and complex numbers, from which rise the mathematical wonders that make the world go round. This dispels the myth that such simple things are also simplistic; on the contrary, they are quite profound, one being able to argue that they lie at the very core of human thought.

But what if we defined numbers, and for the sake we will limit ourselves to natural numbers in this article; what if we defined numbers in a slightly different way? We could name it "constructivistic", as in building the concept and/or structure of numbers in an axiomatic way, starting from almost nothing at all1.

Let's start from a set called \(\mathbb{P}\)2, consisting of objects which we will define in the following way:

- \(Z\) is the Peano "zero": the smallest natural number there can be. We could theoretically choose any other number to be our "smallest number", but then that wouldn't make much of a difference, would it? Therefore \(Z \in \mathbb{P}\).

- For any given element in \(n \in \mathbb{P}\), there exists \(n' \in \mathbb{P}\), defined as \(n' = S(n)\), where \(S\) is an endomorphism over \(\mathbb{P}\). In other words, \(S : \mathbb{P} \rightarrow \mathbb{P}\) is a morphism which generates (unique) elements of \(\mathbb{P}\). It also has the effect of imposing an ordering on \(\mathbb{P}\), which is of course very important, but we'll leave this detail aside for now.

Now let's define another morphism, starting from the binary relation \(\mathbb{P} \times \mathbb{P}\), to \(\mathbb{P}\). We will name it \(\text{add}\):

\(\text{add} : \mathbb{P} \times \mathbb{P} \rightarrow \mathbb{P}\), such that

\(\begin{array}{ll}\text{add}(x,Z) &= x \\ \text{add}(x,S(y)) &= S(\text{add}(x,y))\end{array}\)

We can also define a predecessor function \(P\), as follows:

\(P : \mathbb{P} \rightarrow \mathbb{P}\),

\(P(S(x)) = x\).

Notice that \(P\) is a partial morphism: it's actually only defined on \(\mathbb{P} \setminus \{Z\}\), as there is no predecessor for our "zero" object. To make \(P\) a total function, we'd have to take \(\mathbb{P}\), add the notion of signedness and "double" it with the same elements having the minus sign. The same problems would arise for products and fractions, exponentiations and roots, and so on and so forth. We'll keep things as simple as possible (and no simpler) by remaining in the context of our little monoid over addition.

We can easily show that \(\mathbb{P}\) and \(\mathbb{N}\) are equivalent sets and that the two addition operations are also equivalent3: let's define a morphism \(l\) which "lifts" objects in \(\mathbb{P}\) to numbers in \(\mathbb{N}\):

\(l : \mathbb{P} \rightarrow \mathbb{N}\),

\(\begin{array}{ll}l(Z) &= 0 \\ l(S(x)) &= 1 + l(x) \end{array}\)

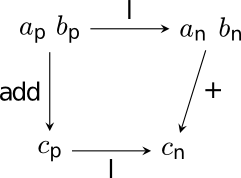

To demonstrate that addition works the same for both sets, we'll start from two arbitrary objects \(a_p, b_p \in \mathbb{P}\) and we'll "lift" them to \(a_n = l(a_p)\) and \(b_n = l(b_p)\) respectively, so that \(a_n, b_n \in \mathbb{N}\). We now have to show that the sum operations over the two objects, and the two numbers respectively, are equivalent. Thus we define \(c_p = \text{add}(a_p, b_p)\) and \(c_n = a_n + b_n\). We have to show that

\(c_n = l(c_p)\).

To do that, we'll bother using a proof mechanism called a commutative diagram. For simplicity, I will represent \(a\)'s and \(b\)'s as pairs and abuse notation a bit, by which I mean that we are applying the lifting function \(l\) on each element of the pair. The final result looks like this:

The diagram commutes, which means that \(l\) can be seen as a functor mapping \(\text{add}\) to number addition4. ▪

A few aspects are worth noting. Firstly, we have shown that natural numbers in \(\mathbb{P}\) are a higher-level interpretation of the natural numbers described as set cardinalities. That is, in addition to describing something very similar to counting using fingers, they also have a sort of structure established by the two constructors which define them. In other words, they also present a deeper algebraic and axiomatic interpretation.

Secondly, both \(S\) and \(\text{add}\) denote, through the presence of recurrence, a kind of inductive reasoning which stands at the basis of the numbers in \(\mathbb{P}\). This leads us to the concept of "catamorphism", or "fold", used to represent these operations over more generic structures such as lists, monoids etc. Numbers are definitely a given, i.e. Gödel's incompleteness theorems show that we possess limited reasoning in regard to them, but they can be used to describe other structures!

Finally, this approach provides an equivalent, yet different framework for the construction of mathematical proofs. While this might seem unimportant for small proofs such as the one above, let's think of the impact for large proofs such as those involving millions of lines of hieroglyphs.

Thus it's not only that miracles happen right before our eyes, but also that these patterns appear all throughout the vast landscape of mathematics, their discovery and the understanding and interpretation of their depth being left to us, the intelligent, and yet so very dumb ones.

In fact such a theory could only start from the same set-theoretical constructs, no matter what other conventions we'd make along the way.↩

From the Italian mathematician Giuseppe Peano, who postulated these axioms.↩

I'll leave the demonstration for \(P\) as an exercise for the reader.↩

The proof for the reverse mapping will also be left as an exercise for the reader.↩